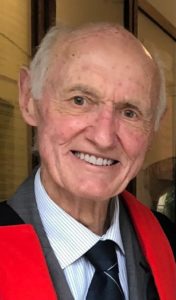

Dr Robert Michael Moor

Dr Robert Michael Moor (28/09/1937 – 10/03/2021)

Robert was the middle child of Donald and Gwendolen nee Whitby and brought up at Avalon, a South African dairy and arable farm. He was educated in Estcourt where he boarded from the age of 5 to 18, his final year spent as head boy. At the senior school the academic standards were high due to an exceptional headmaster, discipline was strictly enforced with the cane and rugby and cricket given high priority. After the completion of his schooling Robert underwent officer training in the Artillery and was awarded the sword of honour. With a ten percent accidental death rate during the training, they learnt to fire heavy artillery with accuracy over 6 miles.

He went to Pietermartizburg University and studied Animal Science for four years.He enjoyed the challenges of climbing in the Drakensberg Mountains and tested himself and other with rock and rope. George Hunter, a lecturer fresh from Cambridge involved him in experiments to transport sheep eggs transcontinentally and this fanned the flames of his scientific curiosity. After university Robert embarked on a northern hemisphere grand tour before marrying his fiancé Felicia Stephens who was his wife for sixty years.

The plan to settle back farming went awry when he attended a meeting in Cambridge and presented the work on the transcontinental embryo transfer experiments. Over a cup of tea he was offered a PhD position at the Animal Research Station , ARS, in Cambridge and thus his future changed. His understanding parents gave their blessing and so instead of farming Bob developed a fascination for how the early fetus signals its presence to the mother and how a new ovulation is initiated if conception fails. Answers to these questions provided Bob with a doctorate, a tenured position at the Animal Research Station and entry into the scientific community which in the 1960s was beyond compare. For a young biologist there can never have been a better time or place to start a scientific career!

Bob spent the 1960s investigating how the ovary, embryo and uterus interact with each other. Focussing on follicular biology offered possibility of uncovering a new route to obtain large supply of eggs for transfer.follicles are the precursors of the corpus luteum and thereby provide a direct link to the ongoing work of the embryo-uterus-ovarian axis.most follicles undergo degeneration and this provided an ideal model to study the then newly recognised phenomenon of programmed cell death. By the end of the decade the group had unraveled some of the ways in which follicles function and had shown how large numbers of eggs can be produced and fertilised in vitro.

These advances, in turn, provided the foundation for studies that were to occupy Bob for the remainder of his scientific career. The studies included work in the molecules that enable chromosomes to separate at meiosis, understanding the means by which oocytes carry out internal audits for chromosomal errors during division, investigating how follicle cells signal between themselves and with the oocyte, and working on the translational mechanisms that control protein synthesis in the oocyte and embryo. Being in a vibrant scientific community enabled him to collaborate on diverse work from freezing embryos, the immunological peculiarities of chimeric sheep to stem cell behaviour in the gut.

The liberal leadership at the Animal Research station during that time encouraged staff to work in laboratories abroad, enabling Robert to work in the USA and Australia, where he was able to work on human tissue. Sadly the ARS closed in 1986 and he transferred to the Babraham Institute where he worked until retirement in 1999. The reputation of the ARS was such that it benefitted from a constant stream of visitors and post doctoral students from all around the world. These scientists brought enthusiasm and added to the intellectual curiosity and vibrancy of the ARS.

Robert chose to focus on his science and his family, nurturing, challenging and encouraging them to aim high. He encouraged rigorous thinking and argument, self deprecating humour and always supported the under dog. He knew that life was hard and the importance of celebrating the good times, he championed good education and encouraged his girls to explore and spread their wings. Robert introduced them to the mountains driving his Morris Minor on annual camping holidays and fostering a love and respect of the great outdoors.

Once his four girls were independent he felt justified in taking risks and had spectacular adventures wild camping in American national parks, canoeing in the Arctic circle in Canada and accepting lecturing opportunities that would enable him to explore the globe.

He was honoured to be elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. He invested his time and talent in the Royal Society, becoming the ambassador to NATO, which took him throughout Europe and beyond to places as exotic as Kyrgyzstan to nurture local scientific talent and explore the mountains.

In his later years he researched and wrote a book, Journey to Avalon, chronicling the shadowy figures of his family over generations. This beautifully written and researched tome is a lode stone for present and future family members as well as a great read as it crosses continents, chronicles adventures and charts how actions ripple and reverberate down the generations.

He continued to cycle into town from his home in Girton, participating in Cambridge University life and latterly developed an interest in Geopolitics and Geology. Robert was a frequent visitor to the University library for his research and the pure joy of being there.

He died peacefully at home surrounded by his family. He is survived by his beloved wife Felicia, his daughters, (sons in law and grandchildren): Catherine (Gora, Anna and Ben ), Jennifer ( Emmanuel, Sam, Charlotte, Max) , Elizabeth (James, Emily, Sophie) and Diana ( Richard, Megan, Matthew, Ffion) and a tortoise.